After US missile strikes, can Tillerson find common ground with Russia in Syria?

The prospect of US-Russian cooperation to defeat

the Islamic State (IS) and al-Qaeda in Syria, a top priority of Donald

Trump’s presidential campaign, may be on life support following US

missile strikes on a Syrian air base April 7.

In a letter to US congressional leadership April

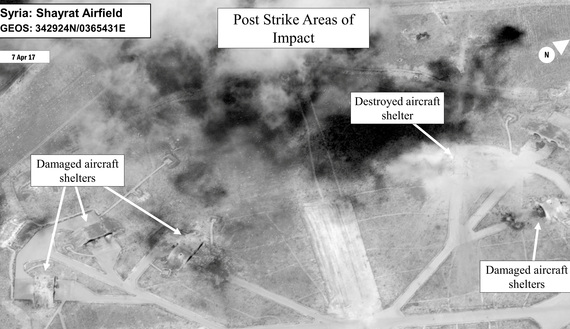

8, President Trump said the purpose of the missile strikes on Syria’s

Shayrat air base was “to degrade the Syrian military's ability to

conduct further chemical weapons attacks and to dissuade the Syrian regime from using or proliferating chemical weapons.”

US Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley warned that the United States is “prepared to do more, but we hope that will not be necessary.”

Following the US missile attacks, United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres appealed “for restraint to avoid any acts that could deepen the suffering of the Syrian people.”

Whether the events of the past week serve to

strengthen US interests in defeating IS and bolster a Syrian political

transition depends on the impact of the US missile strikes on deterring

further chemical weapons use; the outcome of US Secretary of State Rex

Tillerson’s meetings in Moscow (he is to head there April 12);

and the actions of US regional partners who may see an opportunity to

rekindle support for regime change in Syria via proxy forces.

First, with regard to chemical weapons, if the

Syrian government indeed used chemical agents, and especially sarin, as

was first asserted by the Turkish Health Ministry,

there is a question as to whether the limited missile strikes are

adequate to deter further chemical use by either the Syrian government

or terrorist or armed groups who may have that capability. Although the

Syrian government denied using or even possessing chemical agents, the US intelligence community assessed with a “very high level of confidence,”

according to Tillerson, that Syrian aircraft from Shayrat air base used

chemical weapons, perhaps sarin gas, in Khan Sheikhun on April 4. The World Health Organization

reported that at least 70 people were killed and hundreds affected by

the likely use of highly toxic chemicals, and subsequent estimates of

casualties have pushed the numbers even higher. The Organization for the

Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW)

has begun an investigation to “establish facts surrounding allegations

of the use of toxic chemicals, reportedly chlorine, for hostile purposes

in the Syrian Arab Republic.” An investigation by the OPCW-UN Joint Investigative Mechanism last year concluded that both the Syrian government and IS had used chemical agents in 2014 and 2015.

While the quick response may have served to send

a signal of American resolve, especially while Trump was meeting with

Chinese Prime Minister Xi Jinping to discuss North Korea, a pause to

develop an international consensus and verification on Syrian

culpability might have offered, and may still offer, an opportunity for

an even more robust response.

Second, with regard to Russia, although both Trump and Russian President Vladimir Putin had hoped for a new chapter

in US-Russia ties, including in Syria, Tillerson arrives in Moscow this

week with the balance tilted toward crisis rather than opportunity. A press statement

from the office of Putin on April 7 labeled the US strikes on Syria as

an “act of aggression” and declared that the “Syrian army has no

chemical weapons.” Moscow suspended the US-Russian de-confliction

agreement in Syria, increasing the risks of inadvertent military

escalation. The United States, via the de-confliction mechanism, had

given Russia short warning of the US missile strikes in order to avoid

or minimize casualties.

Putin has given top priority to re-establishing

Russia as a regional power in the Middle East. His backing of the Syrian

government boosted his reputation as a credible partner, and he will be

loath to lose face. Putin has absorbed the lessons of 2011, when his

government acquiesced in a UN resolution authorizing military

intervention in Libya, which led to Libyan dictator Moammar Gadhafi’s

overthrow. Russia’s ties to Iran have gone from good to even better as a

result of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s visit to Moscow last

month, as reported by Maxim Suchkov,

and shared solidarity in support of Assad. The Russian president may be

considering his own escalatory steps in Syria, such as reinforced

military deployments or even a Russian no-fly zone, or the equivalent

thereof. The US secretary of state faces a potential buzz saw when he

arrives in Moscow.

Tillerson, with his experience of difficult and

successful negotiations in Russia as CEO of ExxonMobil, may be

well-suited for the task of trying to get US-Russia ties back on

track. Both countries seek the defeat of IS and terrorist groups; that

has not changed. On April 3, the day before the attack on Khan Sheikhun,

Trump had spoken by phone with Putin to condemn the terrorist attack in

St. Petersburg and reiterate a shared commitment to defeating

terrorism. The two sides can also reiterate and strengthen their

commitment to prohibition of the use of chemical weapons, which is

essential to send a clear message to both the Syrian government and

terrorist groups that may have access to them.

Third, there is the matter of whether the

administration’s strike to deter further chemical weapons use will be

interpreted in the region as a sign to resurrect the potential for

regime change in Syria via proxy forces. Tillerson hinted at a potential

shift on Assad when he said, “I would not in any way attempt to

extrapolate that [the US missile strikes] to a change in our policy or

our posture relative to our military activities in Syria today,”

while adding that a Syrian political process should “lead to a

resolution of Bashar al-Assad’s departure.” Just last week, however,

Tillerson had said that Assad's status “will be decided by the Syrian people.” Trump said that his “attitude toward Syria and Assad has changed very much” as a result of the graphic and tragic images from Khan Sheikhun.

Bruce Riedel

writes that the US airstrikes in Syria will “raise expectations” in

Saudi Arabia, and that “the royal family will expect an American

strategy to get rid of Assad sooner rather than later. More military

strikes against Syrian regime targets and the Iranians are what the

Saudis want to see.”

But “aside from money, the Saudis have little to

add to a campaign against the Assad regime and its Iranian supporters

in Syria,” Riedel said. “The kingdom is bogged down in Yemen,

and the Royal Saudi Air Force has its hands full with bombing the

Houthi rebels and the forces loyal to former President Ali Abdullah

Saleh. Saudi air defenses are absorbed in stopping missile attacks

on Saudi cities from Yemen. Also, the kingdom has been very averse to

using its ground forces — either the regular army or the Saudi Arabia

National Guard — inside Yemen and is even less likely to send them to

the more distant Syria. Saudi intelligence is very good at fighting

terrorism at home but has no experience in covert military activities

like Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps' Quds Force. … If the

cruise missile attack is a one-off and not followed by more aggressive

American military action, Riyadh will be bitterly disappointed. It will

still cooperate on confronting Iran in the Gulf and in Yemen, but its

high hopes that someday, somehow, America will rid Syria of Assad will

be again crushed. If the administration is loose in its rhetoric about

how far it is prepared to go in Syria in getting Assad out, its words

will come home to haunt the relationship with the kingdom.”

Amberin Zaman explains how the chemical attacks and the US response may be revising calls for Assad’s ouster, reversing a slow

but discernible trend. While most mainstream press accounts continue to

refer to the armed groups there as “rebels,” with its connotation of

“freedom fighters” or liberators, Idlib in fact remains, as we have

covered in detail, under the control of a “motley crew”

of Jabhat al-Nusra holdovers, Salafi fellow travelers such as Ahrar

al-Sham, and Turkmen and other armed gangs backed by Turkey and others. This column last month explained why Idlib, rather than Raqqa, may be an even more decisive fault line for Syria’s future. Al-Monitor has been one of the few publications to regularly cite the 2016 Amnesty International report, “Torture was my punishment,”

which documents the reality, and brutality, of the rule of Sharia by

the “rebels” in Idlib and Aleppo. Those advocating regime change in

Damascus should take a hard look at Idlib for insight into possible

alternative futures for Syria.

Finally, in Israel, Ben Caspit

reports that the images of the gas attack in Idlib sparked a

reassessment of Israel’s Syria policy. “After reaching an agreement that

Syria would rid itself of its chemical weapons stockpiles, it seemed

obvious to Jerusalem that Israel was out of danger when it came to the

use of weapons of mass destruction (WMD) against its population. This

assessment of the situation led Israel to abandon existing procedures

to defend civilians from chemical weapons. Until then, every Israeli

citizen received a chemical weapons defense kit from the government,

which included a gas mask and other equipment. It was a convoluted and

expensive setup, which was difficult to maintain (every newborn needs

new equipment, mask filters must be replaced, etc.), but it remained in

force as long as Israel felt threatened. And so, ever since 2013, this

defense procedure was abandoned, and the manufacture of gas masks in

Israel came to a halt. The April 4 incident in Idlib raises questions

about that decision,” Caspit writes.

“And there is another issue,” Caspit continues.

“Who can now assure Israel that Assad has not managed to transfer some

of that residual nerve gas to Hezbollah? A transfer of chemical weapons

can be very low key, without any long convoys or heavy trucks. Hezbollah

could then use Iranian technology to install the gas on its missiles.

The result would be a very different Hezbollah than what Israel has been

used to until now. … These horrific scenarios still sound unfounded,

but in the Middle East, unfounded scenarios sometimes turn into

reality.”

Al-Monitor

Labels

English Articles

.jpg)

USA THE CANCER OF THE PLANT -ISRAEL IS THE METASTASIS CANCER.

ΑπάντησηΔιαγραφή